You know that little inkling you get that something somewhere isn’t right? It’s a skill that really good datacenter managers develop. Almost Jedi-like.

I feel a great disturbance in the servers.

Well, today was not one of those days. Today was more like when you know your house is on fire because of all the smoke, flames, firetrucks and especially the alarms going off.

“We just lost another one. We’re at 69% of power supplies on the Cisco appliances.”

“That’s good right? We’re still above 50% so, we haven’t lost any servers yet, right?”

“Well, it WOULD be good if the power supplies would fail uniformly. But, we’ve lost both the primary and the secondary in several chassis.”

“Do we even know how much is down?”

“We’re working on it. . .There went two more. We’re at 63%.”

This was a full-on meltdown. And the frustrating part was that we had no idea why our power supplies were just falling over dead. By the time the event was over we had lost over 50% of the Cisco power supplies in our primary datacenter. Interestingly we lost none in any of our five other datacenters.

Putting things back together involved stripping out the bad power supplies, reshuffling our good ones, pulling every single backup from across the enterprise and shutting down our lab machines so we could rob them. Then, we ran with a single power supply in each device until Cisco could get us more. Getting several dozen power supplies put a bit of a strain on their production.

Now we got to play detective. Why did more than 90 power supplies suddenly decide to give up the ghost at the same time? We sent several of the fried power supplies off to Cisco for analysis and we started looking at the design of our datacenter.

In addition to our other datacenters, none of the other high tech companies had any problems. A good friend is the Global Datacenter Architect for a global company with a local datacenter and he reported their datacenters were fine. . .he also said they didn’t have any spare Cisco power supplies since their architecture was different.

The first thing we looked at was to see if there was any difference between the failed power supplies and the ones that didn’t fail. Many were from the same manufacturing facilities and had been installed at the same time. Some of the failed power supplies were old, some were almost brand new.

We looked at the physical layout of our datacenter. Living in a desert state we cool with outside air. Could something have gotten into the air intake? Nothing unusual, however we were only a couple of miles from a coal fired power plant. Why it should affect us today was anyone’s guess.

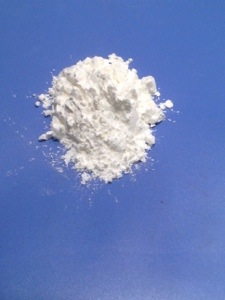

One thing we noted was that inside all our components, both the good ones and the bad ones there was a fine white dust. That dust had been in the datacenter for as long as anyone could remember. We’d install new cabinets and after a few weeks the tops would be covered in the dust. We never could find a source for it, and since it had been there for years, we looked elsewhere for our culprit.

We checked the calendar and noticed that exactly a year earlier we had a similar failure. It was July 6, two days after the big Stadium of Fire, 4th of July celebration. The previous year we also had a failure right after the Stadium of Fire celebration. We never figured out the cause of the previous failure. Could it be fireworks smoke that got sucked in the air intake?

We were successful in pinning down one of the contributing factors: humidity. A huge summer rain storm had rolled through and the humidity in the datacenter spiked into the 70-80% range. It’s normally in the under 20% range. One of the dangers of cooling with fresh air. Normally, Utah’s desert climate gives us nice dry air, but when Mother Nature brings the rain, there’s little we can do.

Meanwhile the Cisco analysis was going on all around the world. We’d get weekly updates from Germany, San Francisco and sites around the US. It was very telling that while ALL the Cisco power supplies did not fail, all the power supplies that failed were Cisco power supplies. IBM, HP and NetApp ran just fine.

We replaced the burnt out power supplies, but continued to pour over temperature, and server logs. Finally Cisco came back with their tentative findings. It was the dust. The dust combined with high humidity caused a condition where a capacitor could arc in the power supply. They had never seen this behavior anywhere else in the world. And their best guess was that it was the dust.

So, where did the dust come from? The datacenter was not particularly old. I think it’s less than 10 years old. And if you’ve ever been in a datacenter, they are not particularly dirty places anyway. We checked the air intakes again, but the dust wasn’t on the intake screens. It was being generated from inside the datacenter.

We checked incoming packages. We moved a lot of equipment in and out of the datacenter, but the packages were not particularly dirty, and the dust they did bring in wasn’t white. We checked under the floor. Datacenters are cooled through the floor. That’s why they have that weird “tile” look. We pulled up the tiles and checked the AC units and the area under the floor. But, the dust was coming from something above the floor.

We all had our own theories. Most of them pretty flimsy, since the facts we had to go on were pretty thin.

Finally, a chemistry professor at the local university solved it. He analyzed the dust and discovered it had the exact same chemical makeup as the powdered cleaning solution our maintenance crew used. I think it was Sodium Bromide.

They would mix the powered cleaner in water and then mop the floor. When the water evaporated it would leave a trace of the cleaner behind. As we walked around the datacenter the cleaner would turn to dust and become air born. So, the more we cleaned, the dirty it got.

Once we found the problem the solution was simple. We quit using that type of cleaning solution. We also learned that CSI stuff is harder than it looks on TV.