It’s not as easy as you would think. There’s five areas you need to consider.

1. Story Craft/Development: Was the story a good lie? Did it begin as apparently truthful and plausible, and then at some point become obviously impossible and bald-faced?

2. Originality: Is it unique? Is it based on a familiar tale, told with an original flair?

3. Effectiveness: Were the listeners entertained? Did they get caught up in the lie? Could this lie be told anywhere in the English-speaking world and anybody would recognize the trnasition from plausible to preposterous?

4. Presentation: Was the lie well told? Were the characters distinctly recognizable and consistently represented through? Did the teller’s use of voice, gesture, facial expression, and eye contact contribute well to the lie?

5. Time Limit: Did the lie stay at 6 minutes or below?

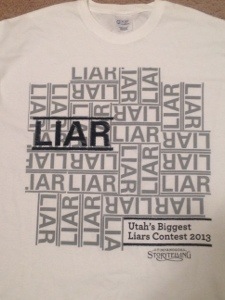

These are the judging criteria for Utah’s Biggest Liar’s Contest, part of the world famous Timpanogos Storytelling Festival. This year, like the last two years, I was invited to be a judge. It’s a chance to reunite with friends and hear some fantastic storytellers. I’m pretty good at public speaking, but I lack the ability to lie convincingly. . .or entertainingly.

Here we see, a guy on the left who is obviously overdressed. Vance Mellen (2013 Best Liar), holding the coveted “Golden Shovel”, Adam Ashton (Runner Up), Daniel Bishop (3rd place), April Johnson (MC and founder of the Utah’s Biggest Liars Contest.)

The winner, Vance Mellen of Lindon, UT explained exactly how to catch Bigfoot. (Reese’s Pieces and Hershey’s Kisses are helpful.)

There’a also a children’s category. Lily Walker did a truly masterful job of explaining how The Force helps with Junior High.

In this setting, of course, telling the best lie is something to aspire to. However, I could not come up with a single instance where telling a lie, and certainly not telling the best lie, was good business practice.

There have been some high profile liars in the past few years. Jayson Blair plagiarized his New York Times articles. James Frey wrote “A Million Little Pieces” and had to later admit to Oprah that large parts of it were made up. David Simpson was inducted into the Oklahoma Cartoonist’s Hall of Fame and was later found to have plagiarized many of his political cartoons.

But, what about the small acts of larceny? After all, wasn’t that an idea that was presented in a brainstorming meeting? How can we say who actually thought it up? And didn’t we sort of come up with that idea during a conversation where we were both contributing ideas?

While at Microsoft, I worked on a team with John, a guy who had written a couple of books. It quickly became obvious that John was most interested in John. At one point I was talking to him about an idea I had for how to restructure the team. John and I were team members, but Microsoft has a very democratic management structure in many ways. I hadn’t finalized my idea, but I wanted John’s opinion on it.

About a week later, I said,

“I had another thought on that team reorg.”

“Oh, don’t bother. I already suggested it to management and they shot it down.”

Sure it wasn’t a big deal. It was a pretty minor subject in the whole scheme of things. So, why do I still remember it 15 years later? Maybe it’s because I’m still upset. But, I think it was the blatantness of it. Had the idea been accepted, John would have been quick to claim credit. If I were to later try to tell people the truth, I’d look like I was trying to steal HIS idea.

It changed our relationship. I no longer shared ideas with John. I started questioning ideas that he presented. Were they his own idea, or was he taking credit for someone else’s work? It also made me consider my conversations with others. Especially when I got into a management role, I made a point of making sure that I gave credit where it was due. As a result, my teams were always comfortable sharing ideas for improvement. As we implemented them and the team did better, we all looked better.

Truth is always the best policy. Leave lying to the professionals.